News Story

Dr James Yoo: Bioprinted Tissues To Be Implanted Within 10 Years

While news about bioprinting has been on the rise, our understanding of the possibilities it offers is still limited. In fact, if you think things are confusing in the industrial additive manufacturing sector, the applications of 3D printing in the medical field – although possibly even more promising – are still even more unclear and hard to classify. Let alone those specific to the bioengineering and regenerative medicine segment.

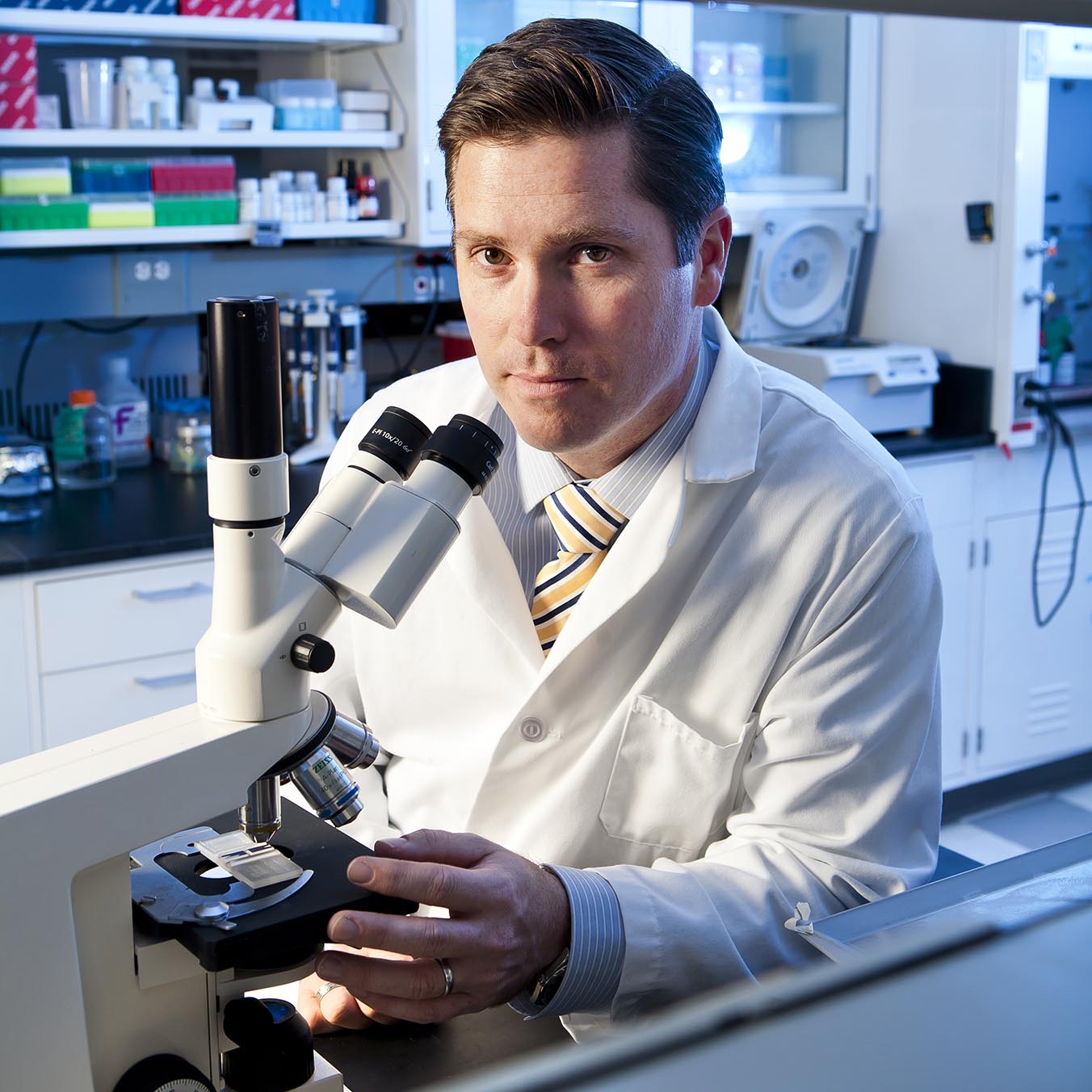

That is, unless you are one of the primary global experts in the field. 3DPI caught up with James Yoo, Professor, Associate Director and Chief Scientific Officer at the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine (WFIRM) (also cross-appointed to the Departments of Physiology and Pharmacology and Biomedical Engineering), ahead of his participation as a speaker at the upcoming Inside 3D Printing Conference & Expo in Santa Clara, California. His clear cut answers on his current work offered some fascinating insights into the state of this technology and the future of tissue and organ 3D printing.

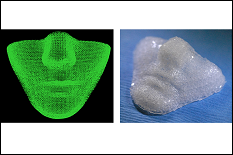

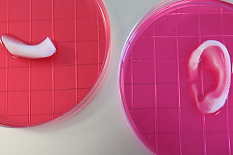

“We are an institute that focuses on clinical translation and all of our efforts are aimed at developing new therapies to improve the lives of patients. Currently, we are working on a wide variety of 3D printing projects,” Dr Yoo told us. “As part of the Armed Forces Institute of Regenerative Medicine, a federally funded effort to apply regenerative medicine to battlefield injuries, we are focusing on printing the components of complex tissue, such as muscle, bone and cartilage, and combinations of these tissues, for facial and skull reconstruction.”

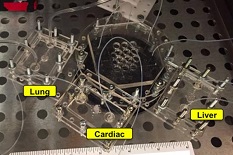

One very interesting, ongoing project is the “Body on a Chip” program, funded by the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, which combines bioprinting and drug testing procedures. “We are working to print miniature hearts, lungs, blood vessels and livers that can be linked into a system to test the effects of drugs. It has the potential to reduce the use of drug testing in animals. Other projects include work to print ovarian tissue and nasal septum.”

WFIRM is known for successful clinical translation and, over the past few years, has demonstrated that lab-built organs (not necessarily 3D printed ones) can function quite well in patients. “Engineered bladders, vaginas and urine tubes that we engineered by hand have been successfully implanted. 3D printers,” Dr Yoo clarified, “offer the opportunity to scale up this process; they can very precisely combine cells and materials into the desired shape. The replacement tissue or organ can be designed on a computer using a patient’s medical scans.”

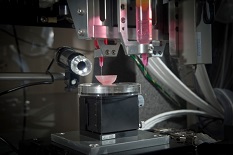

The lab uses a different range of 3D bioprinting technologies and Dr. Yoo is aware of other commercial technologies “There are currently three main printer types commercially available that can be used to deposit and pattern biological materials – inkjet, micro-extrusion and laser-assisted. The printers we use at WFIRM,” Dr too told us, “were designed and built in-house. We use an integrated system that allows for the printing of both solid and flexible materials.”

The real key, just as in the “traditional” 3D printing industry, is materials. “Many people do not realize that biomaterials is a science in itself. The ideal material must not only be printable, but also must be compatible with the body and support cellular attachment, proliferation and function. Also important is how quickly the material will degrade in the body. Material selection must be based on the mechanical properties needed for a particular structure. We work with a wide variety of materials including collagen and polycaprolactone.”

This is the state of the art of bioprinting, a science and process that holds amazing promise and yet is only at the very beginning of the exploration into what will truly be achieved. Some applications, such as drug testing, are already a reality in their early stages, while others are farther down the road. However, Dr. Yoo, like other experts in the field, are quite confident that simpler tissues and organs will be commercially available soon enough. “Certainly, simpler printed tissues, such as bone and muscle, will be implanted first. Within the next 10 years, we expect clinical studies to be under way for simpler tissues such tissues. The timespan for printing more complex organs, such as the kidney, will be much longer.” As with everything else in 3D printing, it seems only a matter of when.

Published November 7, 2017